The

author and son, ready to climb into their Coot amphibian and fly

off to Canada.

TO THE BAY

It’s difficult to control my tension as I open the throttle and begin to accelerate down the runway. I turn for a fleeting glance at Pascal (my son) beside me; he is excited too. He waves to his mother, standing by her car, as we gather enough speed to lift off. Then I come back to important details in the cabin: adjust propeller back to 2500 rpm, manifold pressure to 25", trim for steady climb, and retract the landing gear.

It is mid-June 1997, and we are departing Middleton Airport, near Madison, Wisconsin, heading for James Bay, in north-central Canada! (See Map) You might wonder why we would ever want to fly off to a cold, wind-swept bay where Henry Hudson was cast adrift in a dinghy in 1611. The reason is, I am actualizing a boyhood dream that my father started 42 years ago. His gift to me, on graduating from high school, was supposed to have been a 2-month canoe trip to James Bay, but it never quite happened that way.

When I arrived at Keewaydin Camp on Lake Temagami in July 1955, the director informed me that the trip to James Bay had been cancelled. During the previous summer another camper had drowned while paddling down some big rapids in the Abitibi River, so I was sent on a long, arduous trip across many small lakes instead. As I trudged over long portages in the summer heat, fending off sweat bees and mosquitos, a fellow camper with a bouncy sense of humor tried to encourage me by shouting with gleeful irony: "To the Bay!" Looking back on it now, I recall that in spite of the early hardships, I had a wonderful summer, and I developed character as well as muscle. Even today, whenever I encounter the phrase "To the Bay", I think about making the best out of what seems at first to be a bad situation.

Today the same sort of thing is happening with the weather. Our departure in my homebuilt Coot amphibian was planned for early this morning, on the first day of summer, but the day began with a drenching rainstorm. This tests my patience on the longest cross-country flight I have ever planned. We are 6 hours "late", but so what? All it took was a phone call to my friend, Stewart Farmer in Sault Ste. Marie, to arrange for a later arrival time. Now the afternoon sun is behind us, and the scenery as we fly across Wisconsin and up the Door peninsula is nothing short of spectacular.

After we pass the tip of Rock Island there is no longer any sign that people live on this planet! There are not even any lighthouses. Only wheeling seagulls move against the background of the deserted rocky shores and the calm, deep blue surface of Lake Michigan. The evening sun catches the white breasts of the gulls in creamy flashes as they turn and dive. We let our altitude slip away to enjoy this wonderful scene just a few feet off the water. Our GPS tells us that the gentle tailwind has boosted our ground speed to over 100 mph, and it seems even faster from this wave-top perspective. The feeling of wild freedom and the sheer beauty of this scene passing before our eyes is exhilarating, but also calming.

Are we being reckless, flying along this close to the water? No, not in a Coot amphibian! If the engine fails, all we need to do is hold the aircraft’s attitude steady and raise the nose slightly, as our Coot’s airspeed gradually slows to below 50 mph. The surface of Lake Michigan is so calm this evening that we would barely feel the touchdown. In such an event, however, our two paddles, cellular phone and camping gear packed just behind us would certainly come in handy. But on this magical evening our engine continues to hum steadily, and on the intercom Pascal and I share our delights over this magnificent, moving seascape as we thread our way among the islands to the next airport.

Our printout from the world wide web for Manistique Airport warned us to watch out for deer on the east-west runway. So we keep an eye peeled, and sure enough, just as we near the threshold, a lovely doe bounds gracefully across the runway and into the trees on our right! The printout also shows a motel, just across the road from the airport. As we walk in to register, the friendly owner glances beyond us and asks: "Where’s your car, boys?"

"Oh, we don’t have a car," I explain, "we just flew our plane into the airport across the street."

"Then you must have come in that helicopter that just flew over!" he announces.

Pascal and I look at one another and grin. "That was us alright," I reply, "but the plane is a Coot amphibian, and its pusher propeller just makes it sound like a helicopter."

The next morning the weather is beautiful with light NW winds. We get up early, but since there is no rush to cross the border into Canada before noon, I file an indirect flight plan to Sault Ste. Marie via Grand Island on Lake Superior. We fly NNW over the Bay Island Lake Wilderness Area and look down on the primitive forest made famous by Hemingway.

How he loved to commune with Nature as he fished and camped by those lakes 70 years ago.

Suddenly a stark, cold-looking prison looms out of the forest just south of Munising! The feeling of exuberant freedom that normally accompanies Coot-flying rapidly drains away. Reality sets in like a cold, wet towel as I recall that we still have to lock people away in brick and steel cages in this remote forest. When are we going to find a better way to protect society from the behavior of ‘deviants’ than by incarcerating them to reinforce one another’s negative attitiudes?

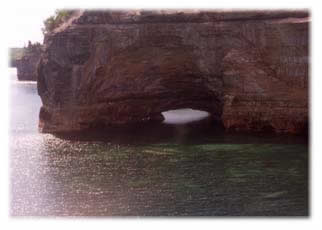

Soon the town of Munising itself shows up. It looks more cheerful, since it seems to relate to Lake Superior, and Grand Island is just ahead to the left. We turn NE along the shoreline and descend to enjoy an incredible view of the Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore. The photograph below provides only a fleeting glimpse of the panorama, for kayakers report that the endless shades of color in the rock and the shifting green glow from the water provide an eerie beauty that leaves a lasting impression.

We fly on to Sault Ste Marie almost in a trance, but we are jolted back to reality when we cut across the Whitefish peninsula and encounter surprising turbulence over the Tahquamenon Forest. This subsides as we return to overfly the water of Whitefish Bay, and we listen to Sault Tower for air traffic as we skirt their control zone and head for the rapids. Pascal asks, "How did the Sault get its name, Dad?"

"The French ‘saut’ means ‘leap’, or sometimes ‘rapids’. Between the Old French spelling and the pronunciation [soo], the French would hardly recognize it now."

As we approach the rapids, we descend to inspect the landing area for floating debris, and to check on the precise location of the Bushplane Museum. Then we turn back, into the wind and current, and touch down in the lee of a huge, moored lake freighter. Pascal points to an arm-waving figure in a bright red shirt running out along a dock. "Is that Stew? He must have heard us fly over!"

"That’s him alright! It’s good to have a welcoming committee amid this bewildering array of docks."

When we reach the end of the dock I shut off the engine before dropping the gear, because any forward movement in the water will prevent the mains from locking down. Then, as the engine starts up again, I just steer us toward the ramp with water rudder (while still floating) and with brakes (after the wheels touch the ramp) until we’re up on top of the wharf. What a slick way to enter Canada!

Stew welcomes us warmly but also in an official capacity, for he volunteers at the Bushplane Museum, and he helps us tie down. As we enter the museum I am delighted to discover that Stew’s Coot is almost ready to fly. All it needs are a windshield and a coat of paint. Stew gives us a tour of his plane and the many other seaplanes in the museum. I am so impressed by the stories of their important role in protecting Canadian forests that I break away with much reluctance to close the flight plan and clear Customs.

By 1 PM we are starting to feel hungry, so Stew whisks us away in his air-conditioned Chrysler. My senses force me to notice the marked contrast between the limited comforts of our Coot cabin and the quiet, cool, plush environment of his luxury car. Then I remind myself that this vehicle can’t float or fly. Still, it’s nice to relax in comfort when one has to return to the ground.

Soon we are enjoying a delicious lunch at Stew’s home, made by his charming wife, Ruby. As we sit at the dining table, exchanging Coot stories for up-dates on Canadaian political scandals, I feel very comfortable here, relaxing with my son and old friends in the same town where I had first learned to fly at the tender age of 21. Stew and Ruby take us for a tour of the town later that afternoon. I find it curious that most of the population of the two Sault cities live in Canada (81,000 in Ontario versus 27,000 in Michigan), while the shipping lock activity is almost exclusively on the American side. We visit the only Canadian lock, not operational since 1987, but now being rebuilt for pleasure craft. The entire Canadian waterfront has been developed and significantly improved, but the passage of 38 years has removed all traces of my old flight school on the St. Mary’s River.

The next morning is Monday, and everyone seems to be bustling about. Pascal and I both misplace our sunglasses, but finally we get ourselves organized, and lift off the river into a light westerly breeze for a short hop over to the Sault airport for fuel. Our next destination is Chapleau, but rather than head there directly, we fly straight north, enjoying the magnificent scenery along the shore of Lake Superior for the first 15 minutes. There are no clouds, and our hearts are as light as the thermals as we head off into the Canadian wilderness.

The undulating thick green carpet of trees before us reminds me that it’s time to get out my hand-held GPS for finding Chapleau. But before I can do that, I make sure that Pascal is comfortable with the controls. He has flown the Coot before, but only during evening flights over lakes, when the air is still. Now the thermals, though mild, will give any novice a challenge when flying a pusher amphibian. "How does it feel, son? Remember to control mostly with rudder!"

"I’ve got it, dad; no problem." Pascal reassures me that he’s in control, and I know he’ll tell me if he’s having any trouble.

I key the letters CYLD into our GPS. It’s just a little Trimble model, but it leads us right to the Chapleau aiport after an hour. From the air the most notable features of the town are a lumber mill and the airport. I remember as a young man, hearing fisherman say with reverence that they were going to Chapleau, as though they were going to the edge of the world. Thirty-eight years later I see why they felt that way. Highway 129 north from Thessalon crosses #101 and then ends right here; there is nothing north of us but forest and rivers.

I announce our intentions on Unicom and land on the very ample, concrete runway. A ruggedly handsome man, looking rather like Ronald Reagan, comes out to pump the fuel. After introducing himself as Willie and making admiring remarks about our Coot, he asks if we plan to camp on some of the lakes in the region. When we reply in the affirmative, his expression changes to one of concern, and he asks us if we are carrying any firearms.

"No we’re not," I reply, "should we?"

"Why yes, unless you want to be on the menu of some of our black bears! They seem to be developing quite a taste for humans, lately."

"But we’ll be camping exclusively on islands," I explain.

"Makes no difference," he insists, "they’ll smell you from the mainland and swim across to your island at night. You have no idea how vicious they are!" He continues by telling us several ghoulish tales of families attacked in their tents, and parents literally ripped apart in front of their children or vice versa.

Pascal and I are initially intimidated by these remarks, but as Willie continues on his diatribe, now against the inefficiencies of the Canadian government’s socialistic policies, I relax a little. Back in the privacy of our Coot I turn on the intercom and say to Pascal, "Beware of the woeful Willies of this world. It is one thing to be informed and prepared, and quite another to be driven by fears and phobias!"

But Pascal is not entirely reassured by my remark, for he counters with: "Okay Dad, just watch out for those rose-tinted glasses of yours," a reference to an old family joke about my perennial optimism.

"You bet," I reply, adjusting the sunglasses in question as we taxi for take-off to Kapusking. This 1.5-hour flight takes us down the Kapuskasing River and north to the Trans-Canada Highway (#11). The town’s history goes back 200 years as a Hudson Bay Trading Post. It expanded in 1910 when the transcontinental railway came through, and for many years its main industry has been the production of newsprint paper. The airport, a few miles southeast of town, is now deserted except for a reluctant, part-time attendant who pumps our fuel.

It is 1 PM, and we have a good appetite, but there is no restaurant nearby. Fortunately there is a soda machine in the airport lobby, and we dip liberally into the bag of trail mix that I brought along for just such a contingency. However, we are soon joined by several big flies who want to get in on the action, and when we close the canopy, the cabin gets uncomfortably warm.

"Pascal, how would you like to finish lunch in peace at altitude?"

"Suits me, dad. Besides, that’ll give us more time at the Bay."

We don our headphones and start up without delay. In 20 minutes we pick up the Abitibi River, the ‘highway’ we plan to follow up to Moosenee. I pay special attention to the scenery now, because this is what I missed in 1955. Where are those big rapids that took the life of a camper back in 1954? Suddenly we spot a hydroelectric dam, and we are struck by the drastic change in the riverbed downstream.

There is only a trickle of water that wanders through an otherwise empty bed strewn with boulders. This scene continues on for many miles before tributaries join in to provide enough water to even float a canoe, let alone a Coot. The trees gradually become smaller as we continue north, and the vegetation takes on the pale green color of muskeg. The river widens and fuses with the Mattagami to become the Moose River.

Slowly, ever so slowly, our destination becomes distinguishable in the distance. That town on the left bank must be Moosenee, and the sister town on the island in the middle of the river has to be Moose Factory. Wow, that blue line on the horizon is James Bay! I am torn between landing at the airport straight ahead or going off to play in the waves of James Bay. An inner sense tells me to do the former, so I call the tower and set up an approach on runway 36.

The winds are more from the west than north, but I prefer this short concrete strip to the longer but gravel east-west runway being used by the CreeAir turboprop freighters; they sure raise a lot of dust while we park. The airport manager hauls heavy, concrete tie-downs to us with his front-loading tractor, and points to a pair of Sandhill cranes, courting and dancing by the gravel runway just north of us. Pascal dives into the luggage for the binoculars, and we are thrilled to see these graceful birds having such a good time, completely oblivious to the air traffic.

Then I turn to the airport manager with a more serious matter in mind, for woeful Willie, beside warning us of bears, predicted that there won’t be any aviation fuel in Moosenee. The manager admits that he doesn’t have any 100LL fuel at the moment, but he assures us that we will be able to purchase some in the morning. I hope that he will deliver!

We pick up our bags and, seeing no taxis, hike 2 miles into town. About half way there we pass the railway station. As they unload vehicles and other freight off flat cars I realize that Moosenee is at the north end of the line. Most of the people we see here are Native Canadians. We left the frontier of settled Canada back in Kapuskasing. This is another world. This is the beginning of the True North!

The Polar Bear Inn is a white, 2-story building that is clean but distinctly ‘institutional’ on the inside. We have not made reservations, so we’re pleased to find a comfortable room and a delicious supper. That evening we join with 3 others for an informal tour of the town. Our guide, Peter, stops at numerous points of interest that reflect the uniqueness of his town. One of these, shown below, is a boat yard dominated by 3 well-used tugboats. Peter describes how they will soon be readied for launching in the Moose River to tow barges full of cargo to several ports around Hudson Bay. Apparently the residents of these ports have been waiting for their supplies since last August! When I ask why the tugs haven’t left on their missions yet, Peter explains that shipments cannot begin before July 1 at the earliest, because there is still pack ice blocking the upper part of James Bay.

END OF PART 1

PART TWO

The next morning I awaken to an ominous, repetitive clanging sound. I look out our hotel window to see that the wind is quite a bit stronger, and is now coming from the south, causing the floating dock on the Moose River to jerk noisily at its moorings. It’s time to decide whether to push on or take a rest day in Moosinee. I’ve heard tales of other pilots who were fogged in here for days, and I know that a major front will soon sweep across Ontario from the west. It’s just a question of how quickly that will happen. Our next destination is Welcome Lake, about 3 hours south of us, and we decide to make a run for it before the weather closes in.

Pascal and I eat a quick breakfast and take a taxi to the airport; we are hoping for an 8 o’clock departure. We pack our gear and check the plane over, but there is no sign of any fuel. The manager assures us that Freddie (who sells fuel from his truck) plans to fly out this morning as well, and he will surely arrive after a momentary delay. The moments drag into minutes, and the minutes into hours. I can get philosophical about the weather, but this kind of procrastination is very exasperating. Finally, just as I am about to lose my patience altogether, Freddie shows up and prepares to pump his fuel into our Coot. Then he stops and says to me: "By the way, I don’t take credit cards, and I pay dearly for this gas myself, so I’ll have to charge you $1.25 per liter, in cash."

I have to give this pirate credit for having an impeccable sense of timing. Fortunately I have just enough Canadian cash in my pocket. I decide to keep my cool. What’s the point of ranting at a time like this? "You have me over a barrel," I reply, "so fill ‘er up!"

At 10:30 AM we lift off to the south over the town and swing north to take a closer look at James Bay. As we fly over the mouth of the Moose River we notice that the muskeg on either side of us gradually gets thinner and browner, and then the mud turns white with salt as it merges into this vast expanse of blue inland sea.

Ever mindful of the strong south wind, I keep our visit short, hoping to reach Timmins (195 miles away) with the remaining 26 gallons of fuel. We have flown half way to the border of Quebec, so we turn south, using the GPS to monitor our progress. I note with concern that our ground speed is only 75 mph, and with the 2.6 hours worth of fuel on board, we will be flying on fumes over Timmins. Fortunately there is an alternative airport at Cochrane, 40 miles this side of Timmins. I remind Pascal that Freddie has advised us not to land at Cochrane because the runway is short and has obstructing hills nearby.

"Since when did procrastinating pirates start telling the truth?" Pascal asks. What a wise kid! I taught him well. After 2 hours we abandon the GPS and fly along the Frederick House River right into Cochrane, noting that the unobstructed field could have handled a Learjet, let alone a Coot.

I pull up to the fuel pumps and jump out, barely suppressing an urge to kneel and kiss the ground. I look up instead, and see a solid front bearing down on us. Pascal and I study the maps, trying to decide whether to wait out the storm here or try to make Welcome Lake. When the part-time FBO arrives to pump fuel, she helps us to make up our minds. "That’s bad weather comin’! I can call the Polar Bear Camp nearby, and they’ll come right over and pick you up."

I am amused to think of spending one night in the Polar Bear Inn and the next night in the Polar Bear Camp, and I agree with the plan. Minutes later Bill Konopelky, owner of what he prefers to call the Lillabelle Lake Resort, shows up with his truck. He provides extra rope to secure the Coot well as he helps with our gear. We round out the afternoon with fish stories at Bill’s bar, a relaxing soak in his hot tub, a game of pool and a delicious supper. By this time we feel quite spoiled, so we take a 3-mile walk over rough terrain, and return to camp just as darkness, wind and rain descend.

Next day the rain continues on and off. Suddenly a squall hits the camp around noon with winds gusting over 50 mph. Everyone dives for cover. Later, Pascal and I borrow the cook’s car to do some shopping in town. While browsing through some camp books that evening I discover and read a wonderful tome about WWII aircraft.

On the following morning the rain stops, and the Flight Service Station gives us a favorable forecast, especially toward the south, where we’re going. We take off at 9:40 under low scud. As we climb out over the camp we dip a wing to the cook, who kindly drove us to the airport moments before. We skirt the east side of Timmins as we go south under clearing skies, and then head west to pick up a power line that leads us straight to Welcome Lake. The GPS is still a powerful tool for determining the precise distance travelled.

My attraction to Welcome Lake goes back to 1955, when I found 3 charming campsites on its central island. During a return visit in 1964 I was greatly disappointed to find all 3 campsites so inundated with empty American beer cans that I had to clear a separate area in order to pitch a tent. Ever since then I’ve been curious to know how that poor little island was faring. And there it is now, looking cool and green in the middle of the sparkling waters of Welcome Lake!

As we approach the island it comes under our starboard wing, and I adjust the propeller and throttle for a fairly steep turning descent because of the surrounding hills. There are no flaps on a Coot, nor are they needed, for at reduced power settings it will drop like a big white bird out of the sky. As we near the lake I gradually flare the Coot on the lee side of the island, holding it in ground effect over the water until the airspeed slows to 55 mph. It’s a good landing. We tickle the wave tops for a while, gradually settle into the water, and finally we come off the step. I notice a sheltered bay on the southeast side of the island. We taxi in slowly and tail up on shore.

I am impatient to explore the island, so I lead off through dense undergrowth in my shorts and wet sandals. I force my way 3 times to the opposite shore, making a triangular pattern, hoping to cross a trail betwen campsites, or perhaps find a campsite directly. Pascal does his best to keep up, but the thick foliage often closes in behind me as I pass. At last he catches up with me and exclaims, "Dad, your back is being bitten by at least 10 mosquitos!"

"No problem, son, just a mild counter-irritant for the cuts on my legs." We look down, and indeed they are a mess. I push on, but we find not a trace that a human has ever set foot on this island except for the remains of a small campfire on a rocky promontory near the Coot. It is now past noon, so we extract some trail mix and power bars from our packs and enjoy lunch in the peace and tranquility of this lovely island.

As we sit on the rocks listening to the water lapping gently on the shore, we also hear the plaintive "oh Canada--da--da" of the white-throated song sparrow, and I feel relief that Nature has reclaimed this beautiful part of my boyhood memories. Occasionally some mosquitos come out of the trees to remind us that they are still guarding this island against human invaders.

Once more Pascal and I consider our options. We had originally planned to camp here overnight, but that was 2 nights ago. We have used up 2 of our 4 ‘rain’ days, and there is plenty of time this afternoon to continue on to Sault Ste. Marie before dark. Welcome Lake, for all its charm, does not attract us as much as Stew’s home. However, the wind is strengthening, so we will not attempt to fly directly to Elliot Lake with only 15 gallons of fuel on board. We untie the Coot, fly off over the hills and surrounding lakes, and head south along the power line to Sudbury for fuel.

Our climb out from the Sudbury Airport takes us right over the industrial heart of the city. It is reported that the air quality near the nickel mines has improved significantly during the past 30 years, but the mines have left lasting scars on the land. As we continue our journey westward, the intensity of the thermals becomes more noticeable. Pascal kindly offers to take the controls for a while. It is a challenge that he manages well, and it gives me a welcome relief to study the charts and enjoy the scenery.

Our next stop, Elliot Lake, brings back more memories. I landed here at a seaplane base in 1959, during my first solo cross-country flight. I was flying a Piper J-3 Cub on floats at the time, and I remember feeling at the mercy of the gusty afternoon winds. Until then I had flown mostly off glassy water during evenings, and I probably had a false sense of security. Suddenly I realized how vulnerable I was to the vagaries of sudden wind gusts in such a light, underpowered aircraft on floats. Ever since that day I developed a preference for the versatility and security of a monohull amphibian.

Now the old seaplane base is closed, replaced by an airfield with a paved, east-west runway and friendly staff. When we stop briefly for fuel, I ask about the status of the many homes nearby following the closure of the uranium mines. We are told that the government bought them, converted some into condominiums, and sold or leased them at reduced cost to elderly couples who wish to retire in the north. Sometimes Big Brother is good.

As we continue on to the Sault we pass over Thessalon, where I used to work for the Canadian Department of Fisheries on the lamprey eel problem. We had high hopes back in 1959 that we’d solve it, but now I think that the number of lampreys were eventually limited more by natural factors than by our puny efforts with electric barriers and chemical "treatments". How easily we cause, and with what difficulty we correct, the imbalances of nature!

Continuing westward, we hug the Lake Huron shoreline, grateful for the reduced turbulence over water. As we approach the St. Mary’s River I take sort-cuts across the occasional piece of Canadian land, but Pascal strongly objects when I consider doing the same over American soil. He is sure that American jets will be scrambled to intercept us if we do. I humor him, partly because it gives me a chance to fly the same pattern learned from my flying instructor 38 years ago. It feels good to let those boyhood memories flood back, especially at a time like this. Of course, I point out all these things to Pascal, and he listens patiently. I leave the propeller on cruise setting as we throttle back and slowly let down along the eastern boundary of the Sault, and turn into the wind to touch down at the Bushplane Museum. It’s not quite 5 PM, and Stew, working inside, hears us only as we taxi up the ramp.

Two hours later Stew and Ruby hear all about our adventures while we enjoy supper at a charming restaurant on Lake Superior. It’s hard to believe that we dined together just 4 days ago; so much has happened since then, it feels like a week or more. If I found it relaxing to visit with our friends at the beginning of the trip, imagine how content I feel near the end of it. I have to pinch myself to make sure I’m not dreaming! Back at Stew’s home we try a bottle of his home-made wine. We sip it slowly and sleep well that night.

Friday morning we plan our trip home. I call another friend, Bruce Buksyk in Appleton Wisconsin, and arrange to have supper with him. We don’t need to leave until noon, so we take our time with breakfast and help Stew test his Coot engine at the Bushplane Museum before departing. I file for Chippewa, MI, since the Sault field in Michigan is closed for runway repairs. We bid farewell to our gracious host, taxi down the ramp, retract the gear and we’re off!

Clearing customs and refueling in Chippewa is routine, and we continue on to Manistique, as the winds gradually strengthen from the south. During the landing approach to runway 27 we encounter gusty crosswinds, so after refueling we depart on the shorter runway 18. I fully expect to feel tension lifting off a 2,500-foot runway and over a highway with full fuel and baggage on board. What I don’t anticipate, however, is the amount of turbulence we encounter from the headwind as it sweeps up Lake Michigan and burbles over the trees along the shoreline. Wow, this is like a roller coaster with very tight turns!

Things finally settle down at 2500 feet, but now the GPS indicates that the headwind has added over an hour onto our ETE (estimated time enroute) to Appleton. We decide to add a fuel stop at Sturgeon Bay, and we also descend to check the ETE at wave-top height. It’s miraculous! Most of the extra time can be saved if we continue at this altitude. This requires real vigilance though, with wind gusts this close to the water, and we also have to watch carefully for seagulls. The headwind seems to keep them from hearing us as easily as they did 6 days ago when we had a mild tailwind, but they still manage to avoid us with plenty of room. Nonetheless, when flying near birds it's always nice to have a pusher propeller. And down close to the water the scenery is fantastic!

As we fly into Sturgeon Bay I plan ahead for expected turbulence near the south shore, and apply full power to gain plenty of altitude. Wow, it's still bumpy up here as well! It’s good that runway 20 goes directly into the wind, and the Coot is so easy to land if you just fly it onto the runway. The FBO is very friendly, and we soon discover that there is another Coot on the field, recently purchased from its builder in Minnesota. Unfortunately it is tucked away in a hangar, so we’ll have to plan a proper visit the next time we come up this way.

We continue south along the Fox River Valley as the winds of the late afternoon gradually lessen. The flat farmland is interrupted only by industry along the river, especially pulp mills that spew their effluent into the warm haze. My radio becomes erratic near Appleton, an unfortunate coincidence, because it also balked here on our way north last weekend. After we land the FBO walks over to us, introduces himself and says: "I like your pretty airplane, but we’re going to have to reach an understanding if you plan to return with a radio like that during a busy flying season like the EAA convention."

I reassure him that the radio will be replaced during the plane’s annual inspection this winter, a promise made to myself with even greater resolve when Bruce shows up a few minutes later, saying, "Gee Richard, that Genave radio of yours belongs in a museum!"

I accept Bruce’s gibe easily, of course, and also his invitation to come with him to inspect his Coot project. We drive a few miles south to Neenah, where we find it, as with many other Coot-builders, tucked inside an ample garage and displacing the cars into the driveway. His Coot is over half-built now, and Bruce is dealing with the challenge of mounting an unusual engine: a rotary design taken from a Mazda. It has a favorable power/weight ratio, but it requires a gear reduction unit, a fixed pitch propeller and a radiator for water cooling. I admire Bruce’s cheerful confidence, making significant departures from the designer’s plans, yet I think he will be successful.

Later we dine at a pleasant restaurant that specializes in buffet suppers; it is obviously very popular with Appleton residents. Bruce, midway in age between Pascal and me, relates well with both of us as we share stories and dreams, and the hour arrives all too soon when we should depart in order to be home by dusk. Pascal does the honors this time and flies the final leg back to Middleton. He admits it is effortless, now that the breeze has died. We look down on Green Lake and admire the peace and tranquility of it all from 2000 feet; the wakes of boats towing water-skiers make lazy spiral patterns, and other parts of the lake glisten in the setting sun.

I lean back in my seat and stretch like a contented cat. Only one thought comes to mind right now. Where in the world will I fly next year to have a trip that might top this one?